Collisions

In many games, collisions are the main driver of gameplay. Touch the coin to get points, fall into the pit and you die, reach the end to win the level, pass a door to trigger a cutscene. All of these depend on collisions. In this tutorial we will implement a very simple collision detection mechanism that is nonetheless powerful enough to enable the functionality we need in most 2D games.

Axis-Aligned Bounding Boxes

An axis-aligned bounding box (AABB) is a rectangle whose sides are oriented to be parallel with the X and Y axes. It is used to define the collision boundaries of a game object. In the following, the blue and red boxes represent the bounding boxes for the knight and troll respectively.

A axis-aligned bounding box (calling it bounding box from now on) is defined using two points. Our convention is to have P1 be the lower left point and P2 be the upper right.

In code this is represented with a Box2D which stores

two vectors:

type BoundingBox struct {

math.Box2D[float32]

}

type Box2D[N Number] struct {

P1, P2 Vector2[N]

}Forcing the boxes to be aligned with the axes makes collision checking very easy, essentially four conditionals. Lets say we have two bounding boxes, A and B. Each is defined with two vectors P1, P2 so A has A.P1, A.P2 and B has B.P1 B.P2. The two bounding boxes overlap (collide) if A.P1 is to the lower-left of B.P2 and at the same time A.P2 is to the upper-right of B.P1. Below is an example. Try and work out the other possible scenarios to convince yourself why this test works.

In code this is implemented in the Box2D.Overlaps

method.

func (b Box2D[N]) Overlaps(other Box2D[N]) bool {

return b.P1.X < other.P2.X &&

b.P2.X > other.P1.X &&

b.P1.Y < other.P2.Y &&

b.P2.Y > other.P1.Y

}Collision Manager

The Overlaps method allows us to check for collision

between two bounding boxes. In a game we would want to use that to check

for collisions against other game objects. For example, when our knight

swings their sword, we want to check if the sword collides with any

trolls so we can vanquish them. We could do that by iterating over the

scene, getting all game objects and checking for a collision against

each of their bounding boxes. This is somewhat inefficient as not all

game objects will have bounding boxes. A more efficient approach is to

keep a list of all bounding boxes so we can iterate over it quickly to

find collisions. We call this list CollisionManagerAABB

(AABB stands for axis-aligned bounding box).

type CollisionManagerAABB struct {

bbs []*BoundingBox

}Bounding boxes must be created through the

NewBoundingBox method. This ensures that the bounding box

will be recorded in the list.

func (cm *CollisionManagerAABB) NewBoundingBox(static bool, parent GameObject) *BoundingBox {

bb := &BoundingBox{

id: rand.Int(),

static: static,

collisionSystem: cm,

parent: parent,

}

parentXY := parent.GetTranslation().XY()

parentSize := parent.GetScale()

bb.P1 = parentXY.Sub(parentSize.Scale(0.5))

bb.P2 = parentXY.Add(parentSize.Scale(0.5))

cm.bbs = append(cm.bbs, bb)

return bb

}We extend the bounding box to have the static/dynamic distinction. A static bounding box is assumed to belong to a non-moving object such as a fixed level tile, floor or platform. Because it never moves, it can never collide with anything. Non-static colliders, such a player, can collide with it however. We also store a reference back to collision manager for convenience. Additionally, we also record the parent game object that this bounding box is attached on. This is because in the case of a collision we would want the game object that we collided with and not just the bounding box itself.

During initialization we set the position and dimensions of the bounding box. The position is that of the parent game object. We add and subtract half the parent’s size to get P2 and P1. This will make it so the bounding box matches the size of the parent game object exactly. If we don’t want that, if we want the bounding box to be a bit smaller than the game object for example, we can we can fine-tune the position and size using the translationAdjust/sizeAdjust variables and utility methods that we will see in a bit.

type BoundingBox struct {

id int

static bool

math.Box2D[float32]

parent GameObject

translationAdjust math.Vector2[float32]

sizeAdjust math.Vector2[float32]

}To check for collisions we simply iterate over all bounding boxes in

our lists and call Overlaps.

func (cm *CollisionManagerAABB) CheckCollision(bb *BoundingBox) []*BoundingBox {

if bb.static {

return nil

}

collisions := []*BoundingBox{}

for _, other := range cm.bbs {

if bb.Overlaps(other.Box2D) && bb.id != other.id {

collisions = append(collisions, other)

}

}

return collisions

}Static bounding boxes automatically return zero collisions because they do not collide with anything by definition. This is a massive performance boost because in many cases the number of static colliders is much larger that dynamic ones. Consider the following scene from Super Mario Bros.

Mario and the three goombas have dynamic colliders. The tiles (I count 36) and the two green pipes are static. On each frame, Mario and the goombas need to do collision checks against each other and against the static objects. The collisions allow mario to move around, jump on tiles and pipes and stomp goombas. Goombas move left and right, bounce of pipes and eat Mario if he is close enough. That takes a total of

collisions.

The static objects don’t need checks (the pipe will never collide with the other pipe for example). If all bounding boxes where dynamic, because we wanted the tiles to be able to move, or the pipes to fall over when the goombas hit them for example, then the total number of collisions becomes:

which is an order of magnitude increase. The moral of the story here is to try and make bounding boxes static if possible.

In BoundingBox, we define the

CheckForCollisions method which checks for collisions of

itself and other bounding boxes. The collisions are turned into a list

of game objects by grabbing each bounding box’s parent.

func (b *BoundingBox) CheckForCollisions() []GameObject {

if b.static || b.parent == nil {

return nil

}

collisions := []GameObject{}

collisionBBs := b.collisionSystem.CheckCollision(b)

for _, v := range collisionBBs {

collisions = append(collisions, v.parent)

}

return collisions

}If an object is removed from the game its bounding box must be

removed as well. In collision manager, we delete a bounding box by

deleting it from the bbs list.

func (cm *CollisionManagerAABB) Delete(bbox *BoundingBox) error {

for i := range cm.bbs {

if cm.bbs[i].id == bbox.id {

cm.bbs[i] = cm.bbs[len(cm.bbs)-1]

cm.bbs = cm.bbs[:len(cm.bbs)-1]

return nil

}

}

return errors.New("Bounding box not found")

}Bounding boxes can delete themselves with their Destroy

method.

func (b *BoundingBox) Destroy() {

b.collisionSystem.Delete(b)

}Updates

As our game objects move in the scene we want their bounding boxes to

stay attached to them. The bounding box Update method does

exactly that. It recalculates the position and size of the bounding box

based on the parent. This handles the parent moving and

increasing/decreasing in size.

func (b *BoundingBox) Update(dt time.Duration, g GameObject) {

b.parent = g

parentPosition := g.GetTranslation()

parentPositionXY := parentPosition.XY().Add(b.translationAdjust)

parentSize := g.GetScale()

b.P1 = parentPositionXY.Sub(parentSize.Scale(0.5).Add(b.sizeAdjust))

b.P2 = parentPositionXY.Add(parentSize.Scale(0.5).Add(b.sizeAdjust))

if RenderBoundingBoxes && b.sprite != nil {

b.sprite.SetPosition(parentPosition.Add(math.Vector3[float32]{0, 0, 1}).Add(b.translationAdjust.AddZ(0)))

b.sprite.SetScale(b.Size())

}

}The two adjustment variables, translationAdjust and

sizeAdjust can be used to fine-tune the position and size

of the bounding box. These are useful in a variety of situations. If our

sprites have transparent borders we might want to decrease the bounding

box size to better match that. We can also make the bounding box a few

pixels smaller than the sprite to make it easier for the player to dodge

bullets (popular in SHMUPs). A game object could also have multiple

bounding boxes. A boss might have a big one that covers their body that

is used to hurt players that get near and a smaller one near their head

that is their weak spot that the players can attack. We can set the

adjust parameters using these methods.

func (b *BoundingBox) SetSizeAdjust(sizeAdjust math.Vector2[float32]) {

b.sizeAdjust = sizeAdjust

b.Update(0, b.parent)

}

func (b *BoundingBox) SetTranslationAdjust(translationAdjust math.Vector2[float32]) {

b.translationAdjust = translationAdjust

b.Update(0, b.parent)

}

The update method accepts the parent object as a parameter which is something that we aim to standardize for all components that we add to game objects (we did the same for the animation component). It’s not strictly needed here because we set the parent in the NewBoundingBox method.

Visualizing

It is very useful to be able to see the bounding boxes during

development in order to properly tune their position and size and to

catch bugs. To visualize our bounding box we will draw a sprite on top

of it. Rendering the bounding box is conditional on the sprite being

there and the global RenderBoundingBoxes being set to true.

The global is a convenient way to switch off all the bounding box

rendering when we are done tweaking/debugging.

var RenderBoundingBoxes bool

func (b *BoundingBox) SetSprite(s *sprite.Sprite) {

b.sprite = s

b.Update(0, b.parent)

}

func (b *BoundingBox) Render(r *sprite.Renderer) {

if RenderBoundingBoxes && b.sprite != nil {

r.QueueRender(b.sprite)

}

}

We can use any sprite for the bounding box but a useful and easy

option is to draw a fixed color sprite with some transparency so we can

see the game object sprite underneath. The

Atlas.AddFixedColorImage function does this.

red, _ := Game.Atlas.AddFixedColorImage(color.RGBA{255, 0, 0, 180}, math.Vector2[int]{1, 1})

redSprite, _ := sprite.NewSprite(red, Game.Atlas, &Game.Shader, 1)

boundingBox.SetSprite(&redSprite)Interesting side-note: The “image” on the atlas is one pixel. We do

this to save space on the atlas. Because our atlas texture is sampled

with the GL_NEAREST parameter, it expands to a constant

color when stretched out to larger areas. If we had set sampling to

GL_LINEAR this would not work.

Limitations

The main limitation of axis-aligned bounding boxes is that they can’t accurately represent all sprites. Consider the following example. When the object is aligned with either X or Y, the bounding box is an accurate representation of the object but if the object is rotated the bounding box no longer works very well.

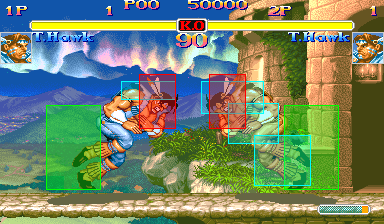

A hacky solution is to add two or more smaller bounding boxes to represent the object. Here’s an example from Street Fighter 21.

This in not the cleanest solution, especially if the game object is animated, in which case we have to move the bounding boxes to match the animation or alternatively spawn new bounding boxes based on the current animation playing. Another limitation is physics. If we have a slanted object, we might like our character to be able to slide on it. This is not possible with axis-aligned bounding boxes, at least without some janky manual coding. A general solution to these problems is to allow bounding boxes to rotate. The downside to that is that collisions of rotated rectangles require more computations and are slower. We might add this feature in a later tutorial.

Collisions in Knight vs Trolls

Lets use bounding boxes to add some new functionality to our Knight vs Trolls game. We will randomly spawn shiny coins for our knight to collect. The coins and the knight will have bounding boxes. When the bounding boxes collide the knight will get the coin. The coin is a game object with an animation component and a bounding set the coin’s bounding box to static because coins will not collide with anything, the knight will collide with them.

var coinFrames = []string{

"data/coin_anim_f0.png",

"data/coin_anim_f1.png",

"data/coin_anim_f2.png",

"data/coin_anim_f3.png",

}

var coinClip = []int{}

func NewCoin(position math.Vector2[float32]) *Coin {

if len(coinClip) == 0 {

var err error

coinClip, err = Game.Atlas.AddImagesFromFiles(coinFrames)

panicOnError(err)

}

c := &Coin{}

c.animation = game.NewAnimation()

c.animation.AddClip(coinClip, Game.Atlas, &Game.Shader, 0)

c.animation.SetAnimationSpeed(6)

c.animation.Run()

c.SetTranslation(position.AddZ(0))

c.SetScale(math.Vector2[float32]{30, 30})

c.bbox = Game.Collisions.NewBoundingBox(true, c)

return c

}Coin has no game logic so it’s update method only updates the animation component and it’s render simply renders the animation. We don’t need to update it’s bounding box since it is static but we do need to render it in case it has a debug sprite attached.

func (c *Coin) Update(dt time.Duration) {

c.animation.Update(dt, c)

//c.bbox.Update(dt, c)

}

func (c *Coin) Render(r *sprite.Renderer) {

c.bbox.Render(r)

c.animation.Render(r)

}Knight is also updated to have a bounding box. The knight’s bounding box is dynamic since we move around and cause collisions.

type Knight struct {

animation game.Animation

idleClip, runClip int

destination math.Vector2[float32]

hasDestination bool

clickEffect *ClickEffect

bbox *game.BoundingBox //NEW

game.GameObjectCommon

}

func NewKnight() *Knight {

//...

knight.bbox = Game.Collisions.NewBoundingBox(false, knight)When the knight steps over a coin we want to print a message. To do that, in knight’s update method we must add a collision check. Knight has a dynamic bounding box so we need to update it to keep it in sync with knight’s movement.

func (k *Knight) Update(dt time.Duration) {

//...

collisions := k.bbox.CheckForCollisions()

for range collisions {

fmt.Println("found a coin!")

}

k.bbox.Update(dt, k)

}Running this code should print “found a coin!” when the knight steps on a coin. Running the code in this state you might notice a subtle bug. The knight is able to pick up the coin even if its slightly above their head. To figure out what is happening we can visualize the bounding boxes of the knight and coins. To do that, we load a sprite to be used as our indicator.

var BboxSprite int

func loadBBoxSprite() {

var err error

BboxSprite, err = Game.Atlas.AddFixedColorImage(gocolor.RGBA{0, 0, 255, 180}, math.Vector2[int]{1, 1})

panicOnError(err)

}And then in knight’s and coin’s constructors we add the sprite their bounding boxes.

func NewKnight(position math.Vector2[float32]) *Knight {

//...

knight.bbox = Game.Collisions.NewBoundingBox(false, knight)

sprite, err := sprite.NewSprite(BboxSprite, Game.Atlas, &Game.Shader, 0)

knight.bbox.SetSprite(&sprite)

}

func NewCoin(position math.Vector2[float32]) *Coin {

//...

c.bbox = Game.Collisions.NewBoundingBox(true, c)

sprite, err := sprite.NewSprite(BboxSprite, Game.Atlas, &Game.Shader, 1)

c.bbox.SetSprite(&sprite)

}Running the code now will show the source of the problem: The knight’s bounding box is too tall. This is because the bounding box matches the size of the parent object which is derived from the size of the knight’s sprite which happens to have some extra whitespace at the top.

We can easily fix that using the scale and size adjustment variables. We move the bounding box 10 pixels down and decrease it’s size by 10 pixels.

knight.bbox = Game.Collisions.NewBoundingBox(false, knight)

sprite, err := sprite.NewSprite(BboxSprite, Game.Atlas, &Game.Shader, 0)

knight.bbox.SetSprite(&sprite)

knight.bbox.SetTranslationAdjust(math.Vector2[float32]{0, -10})

knight.bbox.SetSizeAdjust(math.Vector2[float32]{0, -10})The result matches the sprite nicely.

Just printing a message to “pick” the coin is not that exiting. Let’s

make it so that when the knight picks up the coin the coin disappears

and in its place spawn other coins. We will overwrite the

GameObject.Destroy method of coin to do that. Its default

implementation is to delete the game object. The custom implementation

still deletes the game object (and its bounding box) and then spawns 0

to 4 coins at random locations.

func (k *Knight) Update(dt time.Duration) {

//...

collisions := k.bbox.CheckForCollisions()

for i := range collisions {

collisions[i].Destroy()

}

}

func (c *Coin) Destroy() {

c.bbox.Destroy()

c.GameObjectCommon.Destroy()

newCoins := rand.Int() % 5

for i := 0; i < newCoins; i++ {

pos := math.Vector2[float32]{

X: rand.Float32()*400 + 50,

Y: rand.Float32()*400 + 50,

}

Game.Level.AddGameObject(NewCoin(pos))

}

}We don’t have text rendering yet so you will need to track the score in your head :)

Check the source for this tutorial here.